(The Ringer)- Let me start by making this clear: I want to like President Obama. I want to revere him as one of our nation’s greatest presidents. I want to believe that our imperfect but self-correcting democracy somehow got it right and elected one of its best people to lead it for eight years.

I voted for him — twice — and based on the knowledge I had at the time, I have no regrets. I voted for someone I considered a profoundly decent man, brilliant enough to head the Harvard Law Review, wise enough to oppose the Iraq War when almost everyone else supported it, altruistic enough to devote his skills to community organizing over a plethora of better-compensated options. Beyond that, I identified with the narrative of his life more than I thought possible for any presidential candidate in my lifetime. I am the son of immigrants; his father hailed from Kenya. I am a Muslim; Obama is a Christian, but with a Muslim heritage expressed in his middle name, “Hussein,” the name of the Prophet’s grandson.

We shared not only a narrative, but also a common understanding of what the American Dream means, that what makes America exceptional is not the soil under our feet or the ethnic superiority of its people, but the ideals that we all share. When Obama introduced himself to the world with his keynote address at the 2004 Democratic National Convention, I was rapt. When he said, “I stand here knowing that my story is part of the larger American story, that I owe a debt to all of those who came before me, and that, in no other country on earth is my story even possible,” I felt like every word applied to me. When he said that “the true genius of America” is “that we can say what we think, write what we think, without hearing a sudden knock on the door,” I knew he understood why immigrants like my parents left their homeland in search of a better life.

And I agreed with much of what he tried to accomplish in his eight years in office.

I supported the signature achievement of his administration, the passage of the Affordable Care Act — a stance I can safely say was not shared by most of my physician colleagues. I supported his attempts to raise the marginal tax rate on the rich to pay for an expansion of the social safety net — a stance I can also safely say was not shared by most of my physician colleagues.

While I think he could have done more to reform Wall Street, the Dodd-Frank Act was better than what we had before, and I think his stimulus package in the face of the Great Recession — particularly the bailout of the auto industry — was a vital part of our economic recovery. I supported his gradual and evolving embrace of legalizing gay marriage, and the drawing down of American forces in Iraq and Afghanistan. His decision to launch an operation to find and kill Osama bin Laden, based on convincing but not overwhelming evidence, was a bold and courageous one. His decision to open up relations with Cuba, which showed a willingness to admit that long-standing American policy was not working, will likely yield benefits in the long term.

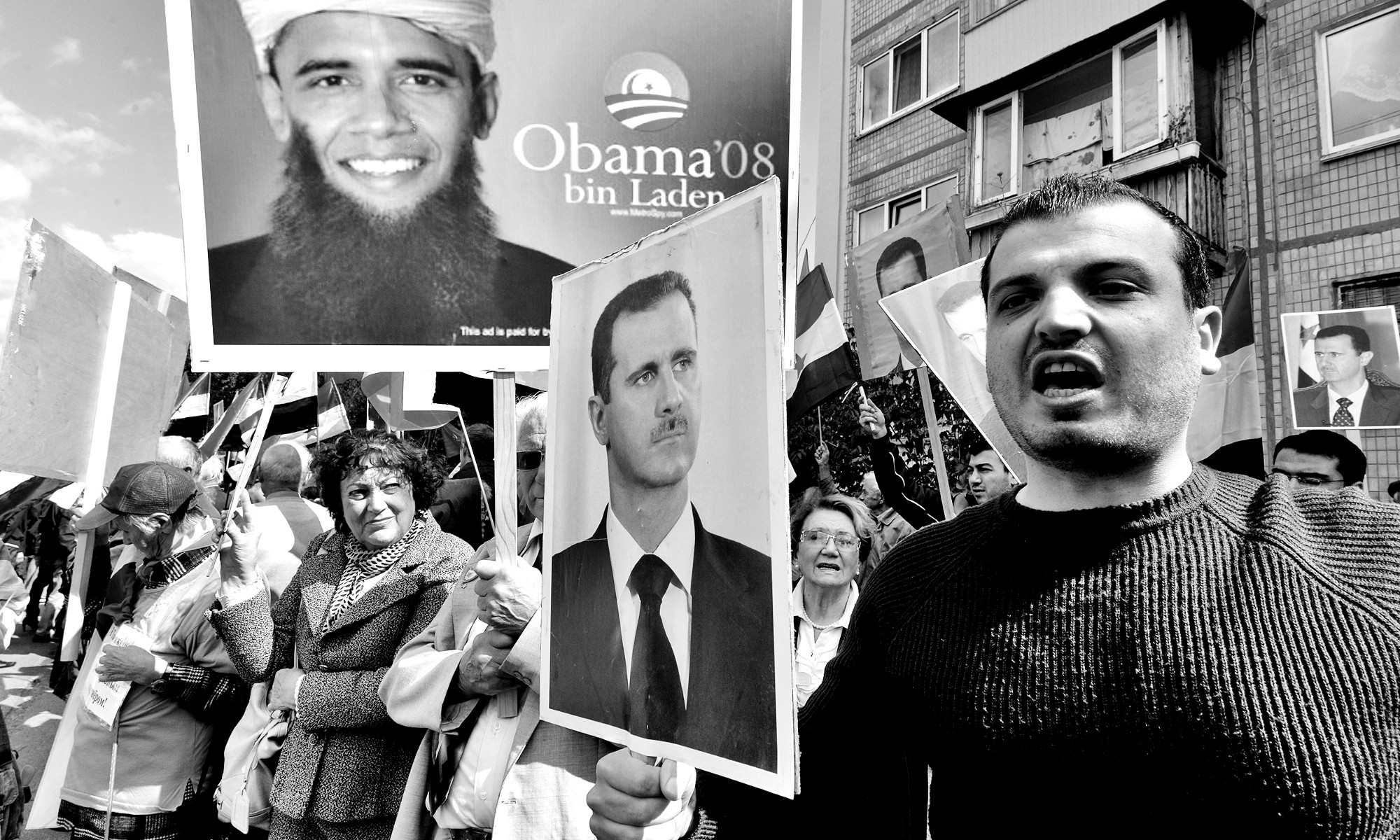

And, of course, he’s done all this despite a Congress that has fought him tooth and nail for six of his eight years in office. He’s weathered the slanderous accusations that he was an illegitimate president born in Africa, a lie that nonetheless aided its primary cheerleader in being elected to become his successor. Barely a year ago, nearly 30 percent of Americans believed Obama to be a secret Muslim, a singular piece of ridiculous nonsense that I find bewildering and — as a Muslim myself — heartbreaking. No president in my lifetime had to deal with as much opposition to his authority, and that Obama got anything done at all in this environment is a minor miracle. As he prepares to leave office, I want to remember him fondly.

Except.

One talking point we’re hearing a lot during Obama’s final days as president is that he avoided a scandal throughout his eight years in office, something no two-term president has been able to say going back to Eisenhower. I respectfully disagree. Nearly six years ago, unarmed, peaceful civilian protesters took to the streets in towns throughout Syria, as they had in Tunisia, and Libya, and Egypt, and Bahrain, as a generation of young Arabs exposed to democratic ideas through satellite television and the internet stood up to demand their inalienable rights from the tyrants who had oppressed them for generations. Within weeks of each other, peaceful protesters had overthrown dictators in Tunisia — a nation that stands today as arguably the most democratic the modern Arab world has seen — and Egypt, where in 2012 free and fair elections produced the first democratically appointed ruler in the country’s 5,000-year history before the nation backslid into autocracy again two years later.

But in the other countries, protesters asking for ballots were met with bullets, and nowhere more so than in Syria by the Assad regime. Unarmed civilians were gunned down, or arrested and tortured before being killed, which led to more protests and more anger, which led to more killing, which led to civilians trying to defend themselves by any means necessary, which led to a full-on armed rebellion.

Rebels of diverse religious and ideological backgrounds were united in opposing a tyrannical dictatorship that compensated for its lack of popular support with military firepower. Hundreds of killings become thousands, thousands became tens of thousands, the vast majority perpetrated by the Assad regime.

And in the face of these killings, and despite considerable support from both sides of the aisle to do something to alleviate the slow-burning slaughter, President Obama chose to basically stand pat. (There have been diplomatic efforts; a trickle of weapons was sent by the CIA to moderate rebels after long delays and with many preconditions; in 2015, a plan to train up to around 5,000 rebels was scrapped after training about five — yes, five.) And no change in the facts on the ground would change his mind. Not the use of chemical weapons to kill more than 1,400 civilians, including many children. Not a death toll that reached almost half a million nearly a year ago. Not the wholesale destruction of cities that now resemble Dresden in 1945. Not the fact that 11 million Syrians — out of a total prewar population of 23 million — have been forced out of their homes. Not the fact that the Syrian apocalypse now ranks as the greatest humanitarian disaster the world has seen since World War II.

In the face of all this, Obama has done next to nothing. And I can’t forgive him for it. I probably never will.

You can’t fundamentally understand what’s going on in Syria unless you understand the root cause: The Assad regime is evil. Many people will condemn this as a simplistic viewpoint, and many more will blanch at the judgmental use of the term “evil.” But another word would only be a cowardly euphemism at best. The Syrian government has ruthlessly suppressed dissent, imprisoning, torturing, and killing its own people, for half a century.

The painful truth for me is that if the Assads weren’t evil, I probably wouldn’t be an American today.

My parents immigrated to America in 1970, a few months before Hafez al-Assad ordered the coup d’état that formalized his position as the unquestioned ruler of Syria. Assad was a member of the Baath Party, who were sort of the Bolsheviks of Syria, a group of socialist revolutionaries who railed against imperialism and government corruption. After they came to power in a coup in 1963, they quickly proved even more corrupt than the government they overthrew, like the Bolsheviks, but with an added dimension of ruthlessness in the service of their ideology. After years of in-fighting, Assad — who had risen from commander of the air force to defense minister — finally defeated all his rivals for power and installed himself as president in 1971. He would rule the country with absolute power until his death in 2000, whereupon his son Bashar succeeded him. (The country holds “elections” every few years — a friend who had visited Syria once told me how he’d happened to be passing by a voting station on Election Day and was ushered inside by men in uniform, whereupon an armed soldier handed him a ballot and instructed him which box to check.) For nearly 50 years, Syria has been under mafia rule.

My parents initially had no intention of staying in America. My dad had just graduated from medical school in Damascus, and they came so that he could complete his residency training and maybe save a few bucks before returning home. They completed the first task in 1975, when my dad finished his cardiology fellowship in suburban Detroit, and then packed up the car and moved with their two young daughters and a 10-day-old baby boy — me — to Wichita, where they planned to stay for a couple of years and work on the second task.

Two years later, my dad visited Syria in preparation for a possible move home. What he saw put an end to his dream of return. The country’s economy was as bad as one would expect from a developing nation that had aligned itself with the Soviet Union. (Even well into the 1980s, my dad had to pay a smuggler from Lebanon to sneak in a new refrigerator for my grandmother.) Assad’s rule was total and enforced ruthlessly, and was aided by an army of secret informants — the notorious “Mukhabarat” — which meant that anyone speaking out against the government, even privately, risked being thrown in prison or worse. With four young children — my brother followed the year after me — my parents made the decision then: They would always love their homeland, but they were American, now and forever. They obtained their U.S. citizenship a year later. They dove headlong into Wichita’s local community with such abandon that as a young child I was barely aware of any identity other than being American. My mom shuttled me to baseball and soccer practice and swim lessons at the Racquet Club; my dad, despite running a full-time medical practice, took enough lessons to qualify for his pilot’s license, went pheasant hunting with friends, and built me my race car for the Pinewood Derby.

In 1981, the summer I turned 6 years old, I visited Syria for the first time. It was a wonderful experience, to see my grandmothers and to meet uncles and aunts and dozens of cousins who previously were only rumors. But it was also a haunting one. Even at 6, I could sense that the air would go out of the room when anything remotely political came up, the way my relatives not only refused to talk about the government but told me to be quiet when I asked questions. And I had questions — like, why were there pictures of Hafez al-Assad everywhere? And I mean everywhere. The first thing you would see when you entered a storefront was a nearly life-size portrait of the supreme leader hanging high on the wall. You’d walk down the street and every 20 feet there would be a poster of him. I asked a relative what would happen if a store didn’t welcome its customers with a picture of their ruler staring down at them. The blood draining from his face was all the answer I got, or needed. I knew the meaning of “Orwellian” and “Big Brother” well before I got to high school.

My parents had hoped that visiting Syria would strengthen my connection to their homeland, but it had the opposite effect. I had already memorized the Pledge of Allegiance and “The Star-Spangled Banner,” but now I knew what “land of the free” and “with liberty and justice for all” really meant. They say there’s no zealot like a convert; well, there’s no patriot like an immigrant, except maybe the child of immigrants who visited his parents’ homeland and encountered everything that America was founded to oppose. I developed a mental block against learning Arabic that persists to this day. The next time we visited Syria, in 1984, I spent most of my free time in my room with my stack of Dungeons & Dragons manuals, devising campaigns I’d never play while counting the days until it was time to leave.

It has been said that a military always fights using lessons from the last war. As a nation, we were terrified of the earlier Gulf War, Operation Desert Storm, because the lesson we’d learned from Vietnam was that we should never send our soldiers into an unfamiliar war zone. As a nation, we thought the later Iraq War would be over quickly because of the lesson we had learned from the Gulf War: These Iraqis are pushovers. And we were reluctant to get involved with the Syrian crisis because the lesson we’d learned from the Iraq War was that we should avoid any kind of direct action — not just boots on the ground, but difference-making tactics like establishing a no-fly zone — to bring democracy to the Arab world. For those of you who still believe that, I intend to convince you otherwise.

President Obama was opposed to the Iraq War from the beginning. In his 2002 speech decrying the impending conflict, a speech that would end up propelling him to the presidency, Obama said — twice — “I don’t oppose all wars.” He also said, “What I am opposed to is a dumb war. What I am opposed to is a rash war.”

The Iraq War was a dumb war. Saddam Hussein was a bloodthirsty, ruthless dictator, and the fact that he no longer walks the earth is the one small solace we can take from the worst foreign-policy decision America has made since at least the Vietnam War. But by 2003, his reign of terror was not at its peak. There was no ongoing rebellion that we could support without sending in soldiers of our own. And it turns out that he didn’t have weapons of mass destruction. (And, of course, he had nothing to do with 9/11.)

Starting in the spring of 2011, Bashar al-Assad’s regime began killings that set off a chain reaction inside the country and now amount to thousands of deaths. There was an active, widespread, grassroots rebellion — the Free Syrian Army, which included a sizable portion of Syrian army forces, from enlisted men all the way up to generals who had defected rather than obey Assad’s orders. Supporting the FSA could have meant that America could have brought about regime change without putting American soldiers in harm’s way. And Assad didn’t just have WMDs, he brazenly used WMDs in the summer of 2013.

Six years ago, the Syrian people had all the ingredients they needed for a successful revolution like the ones that toppled Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali in Tunisia and Hosni Mubarak in Egypt, except for one: a way to overcome the Assad regime’s military might. The Syrian people tried to do this by taking the military out of the equation, as others had in Tunisia and Egypt, by protesting in completely peaceful fashion. Six years later the narrative has been twisted to portray a Syrian apocalypse between two equally armed sides killing each other in a civil war. This cannot be emphasized enough: The Syrian revolution was, at its inception, a completely nonviolent one.

Nonviolent resistance as a tool against oppression holds a nearly sacred status in our shared modern history; the mere mention of “Gandhi” or “Martin Luther King Jr.” can inspire like nothing else. But nonviolent resistance requires one condition to be effective: It requires your oppressors to have some willingness to negotiate. It requires your opponents to accept compromise as a better alternative to burning their own country to the ground. It worked in America, and after the armies sided with the people and refused orders to open fire, it worked in Tunisia and (at least for a time) Egypt.

But it did not work in Syria, because the regime responded to protests with violence from day one. The revolution started on March 6, when a group of adolescents spray-painted anti-Assad graffiti on walls in the town of Daraa. The government arrested and tortured them — kids ages 10 to 15 — for weeks. When their families and friends gathered in town to protest, troops opened fire. Within weeks, protests had broken out around the country. They would be met with a similar response. This had simply been standard operating procedure in Syria for 40 years. The Assad regime has shown over and over again — as it did when it massacred more than 10,000 people in the city of Hama in 1982 — that there is nothing it won’t do, no moral line it won’t cross against its own people to maintain power.

The uncle of one of my closest friends was thrown in prison in Syria in the 1980s.

His crime wasn’t being a democracy activist — it was being the son of a democracy activist. The regime originally locked up the activist, but then decided that rather than make him a martyr, they would simply neuter him by taking a hostage. So they let the activist go and locked up his son — his 17-year-old son — in his place. My friend’s uncle would languish in prison for 11 years before Hafez al-Assad, in a grand show of clemency, ordered the release of a few dozen political prisoners. He found out he was released when he was taken to the prison gate in the middle of the night, wearing only his tattered prison clothes, and pushed out onto the street. He managed to flag a passing taxi, only when he was asked where he was going, he realized he had no idea — he had forgotten his address. Fortunately, the cab driver, recognizing the situation, kindly took it upon himself to drive around for hours until they found a neighborhood that looked familiar, and then a street, and then a building. When he rang the doorbell, his family barely recognized him — no one had seen or even talked to him in 11 years, and he was so emaciated that his ribs poked out beneath his skin.

His naturalized American relatives were able to bring him to Chicago soon after his release in the early 1990s. After immigrating to America, he got married, ran several gas stations, and had four children. I’ve known him for 20 years, but had never heard him utter a word about his time in prison until I bumped into him at the mosque last week and mentioned that I was writing this piece. He took a deep breath and said that he had been thinking it was time to tell his story.

So I asked him.

“Were you tortured?”

He just shrugged his shoulders. “Of course.”

“How often?”

He thought about that for a moment.

“I guess that depends on what you mean by torture. I was beaten by the guards every day.”

“Every day?”

“Every single day.”

He went on, the memories seared into his brain even after decades of silence.

“They broke both of my legs,” he said, pointing to his femurs. “But then sometimes they would pull me from my cell and do other things. They pulled out my toenails,” he said casually, as if it were the most natural thing in the world to happen to an innocent teenage kid, “and they knocked out a couple of teeth.” He opened his mouth and pulled his lower lip down to show me his implants. “And then sometimes,” he paused and grinned, as if at the absurdity, “they attached me to the machine.”

I stood there, silent, cringing at what was sure to come next. I don’t know what was worse: hearing his story, or knowing that, like Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s protagonist, his story is not so different from thousands of others who didn’t get the opportunity to tell theirs.

“They would lay me on the floor naked with my hands cuffed behind my body, and attach electrodes — one to my tongue, the other to my, you know, penis,” he continued. “And when they cranked the machine” — at this point, he let out a harsh, bitter laugh — “my body would lift this high off the ground,” and motioned with his hands 18 inches above the floor.

His phone buzzed and he looked at his text, then suddenly his eyes got wide. “Oh that’s right, I forgot. I have to go, Rany, my son needs me.” His son, nearly the same age as his father was when he entered a nightmare that lasted more than a decade, needed a ride to his driver’s ed class.

There’s one more fact that cannot be emphasized enough, that we cannot allow the victors to rewrite: The Syrian revolution was, at its inception, a generally nonsectarian one. The war today is an immensely complicated affair, with so many sides that it’s hard to keep track of all the groups — rebels opposed to the regime, loyalists committed to the regime, Kurdish nationalists interested in carving out their own state, and foreign powers (Hezbollah, Iran, Russia, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, other Gulf states) meddling on behalf of one group or another. In 2017, though, the core of the conflict is between Assad on one side and Muslim extremists — from Al Qaeda offshoots to ISIS — on the other, which is exactly the way Assad wants it. But the revolution, in its roots, had nothing to do with religion. Many different religious sects have coexisted mostly peacefully in Syria for centuries. The nation was not so much a melting pot as a bouillabaisse or a gumbo — a messy concoction of ingredients that occasionally clashed with each other but usually came together to create something special.

The Assad family comes from one of these religious sects, the Alawites, a small offshoot of Shiite Islam with maybe 3 million adherents in Syria, but really their religious background is irrelevant — power is the only god the Assads worship. What is relevant is that when the revolution began, the Assads tried to turn it into a religious war as quickly as possible, knowing that if they framed their crackdown as one against Muslim extremists and not against ordinary Syrian civilians, the world would turn a blind eye. Rebels have been labeled “extremists” and “terrorists” by the very governments that have been oppressing them throughout human history; if you swallow the tyrant’s narrative unquestioningly, you’ll side with the empire.

So at the same time that the regime was imprisoning protest leaders who were counseling nonviolence and opening fire at unarmed protesters indiscriminately, it announced, in 2011, a handful of amnesties for long-held prisoners — many of whom were known Muslim extremists who preached violence. Assad threw a lit match so he could cry “fire” — and it worked. Within months, alongside the fledgling Free Syrian Army, pockets of extremist groups started to pop up — and unlike the FSA, they were well armed, thanks to a funding network of oil money from the Gulf.

Assad’s strategy was obvious even then, and so was the proper response. I vividly remember, in the summer of 2011, attending a fundraiser for a Democratic congresswoman put together by Americans of Syrian descent here in suburban Chicago. Attendees tried to explain the stakes to her in the naive hope that maybe it would filter up to our president, that the Free Syrian Army, which sought a free and secular Syria, needed support — financial and military — to defeat Assad. And one point stood out above all: Extremist groups were already starting to get weapons thanks to their patrons in the Gulf, and with the death toll at the hands of Assad’s army spiraling upward, if we did not support the FSA, the Syrian people would turn to any group — no matter how odious, no matter how extreme — that would save them from annihilation.

This was Obama’s first miscalculation, to not understand that failing to support moderate rebels ultimately meant empowering the extreme ones. The Assad regime was extremely fragile in the first year or two of the uprising; defections took place at high levels within the government, and large swaths of the army defected en masse. In the summer of 2011, peaceful protesters had taken over the city of Hama, flooding the streets while singing along with the unofficial protest song of the revolution, “Yalla Erhal Ya Bashar,” which translates as “Come on, Bashar, Leave.”

In July 2011, Robert Ford, the U.S. ambassador to Syria at the time, entered Hama with his French counterpart as a show of solidarity with the revolution, and was greeted with flowers and actual olive branches, as hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets to protest the regime. And why not — the White House had already announced that Assad had “lost legitimacy,” sending an unmistakable message that it was in favor of regime change.

American foreign policy has always represented a conflict between our geopolitical ambitions and our desire to live up to our loftiest ideals, and far too many times our government has betrayed those ideals abroad in service of realpolitik. (For examples of this, see the collected works of one Kissinger, Henry.) At its worst, American foreign policy screws up on both ends — as it did when it overthrew the democratically elected government in Iran in 1953, which then directly led to the Islamic Revolution in 1979. But at its best, as in World War II and its aftermath (the nurturing of democracy in Japan and the Marshall Plan), America can flex its muscle in defense of its ideals and advance in the chess game of geopolitics. The Syrian uprising was a golden opportunity to do something both geopolitically advantageous and morally right.

Unlike some other autocratic governments in the region, the Assad regime has never been a friend of America. Its closest allies for decades have been Iran and Russia, which have been two of our greatest foes on the world stage for generations (or at least that will be the case until Friday). Here, suddenly, was a dictatorship facing a rebellion that was pro-democracy and generally pro-American. A grassroots rebellion that wasn’t asking America for a single boot on the ground, just help against the decisive airpower advantage that the Assad regime had — in the form of weapons and/or a no-fly zone — because the rebels had no answer for bombs and bullets from the air. Assad’s military power was too strong for unarmed civilians to resist, but Cold War–era Soviet hand-me-downs would be no match against 21st-century American weaponry.

But President Obama was still learning the lessons of the last war. Despite notable support for arming the rebels from within his own administration — including Ambassador Ford, then–CIA Director (and former commanding general) David Petraeus, and then–Secretary of State Hillary Clinton — Obama chose to give the FSA only token support. They asked for weapons, and instead got MREs.

I can’t argue that aggressively supporting the revolution today would reduce the violence in Syria, splintered as it is into pieces, and with Russian air and ground troops embedded with the Assad regime. But from 2011 to 2013, the country still had a sizable and moderate rebel force, and Russia had yet to establish a significant military presence, meaning that American weapons or American aircraft could have been deployed in support of the rebels without instigating a larger conflict. In the summer of 2013, in fact, the Russians — perhaps anticipating an American military response — evacuated the small military base in Syria that they had manned for decades, and claimed to not have a single soldier stationed in Syria. Only in late 2015 — well after it was clear that President Obama was loath to get America involved under any circumstances — did Russia commence military involvement in Syria with a series of airstrikes (Russia said it was striking ISIS; the United States accused the Russians of attacking rebel positions).

The Iranian government was involved — both directly and through its proxy Hezbollah — with propping up Assad, as Syria is Iran’s only ally in the Arab world. But given that Obama had made securing a nuclear agreement with Iran one of his chief foreign policy goals, pushing back against Iranian ambitions would have given him more leverage to bring Iran to the negotiating table, not less.

By 2013, the FSA was a broken shell of itself, and an extremist group in Iraq decided it was time to expand operations into Syria, renaming itself the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria — ISIS.

The summer of 2013 was also the second and final time Obama was given an opportunity to act, and the second time he made a terrible mistake. In the predawn hours of August 21, the Assad regime’s disregard for human life overwhelmed even their finely honed political instincts, and after years of murdering civilians with no response from the international community, they figured they could launch missiles filled with sarin gas at civilian neighborhoods while people slept.

The attack occurred in the city of Ghouta, just outside Damascus, and killed roughly 1,400 people, more than 400 of whom were children. (Exact figures aren’t available, because the Syrian government has forbidden journalists from reporting this story, and has allegedly killed some — like Marie Colvin — who tried to tell the truth to the world.)

The use of chemical weapons is a violation of the Chemical Weapons Convention (a treaty Syria had not yet signed at the time of the attack), and the mere threat of using them was a pretext to the entire Iraq War. In this case, it was also a defiance of President Obama’s own words the year before: “We have been very clear to the Assad regime, but also to other players on the ground, that a red line for us is we start seeing a whole bunch of chemical weapons moving around or being utilized. That would change my calculus.”

In diplomatic-speak, there is no ambiguity about what “red line” meant. It meant that the use of weapons of mass destruction forfeited any claims of national sovereignty by Assad; it meant that America would be within its rights to launch action — missiles that would take out military installations and runways and cripple Assad’s ability to wage war from the air — which might have been enough to tip the war in favor of the rebels.

Assad crossed the red line, and the world waited for the repercussions. There were none. Obama dithered over what to do until Russian President Vladimir Putin negotiated an agreement whereby Assad would agree to give up his chemical weapons — the existence of which Assad had denied until that point — and submit to inspections by an international monitor. Assad got to stay in power; Obama got a way to save face and claim success without ordering any military action, which is like a prosecutor saying he’s tough on crime because he got the murderers to agree to stop murdering people.

We all share in the blame for the decision to not honor the red line in 2013; Congress was reluctant to support military action, and a plurality (but not majority) of the American public agreed with the lawmakers. But it’s not the job of the American public to understand the global implications of the actions of a dictator in a small, impoverished country. Constitutionally speaking, it’s not Congress’s job either. When it comes to foreign policy, as we have known since Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson rapped for George Washington’s affections in “Cabinet Battle #2,” the president’s decision on this matter is not subject to congressional approval.

Everything since then has been denouement. If Obama wasn’t willing to lend a hand to the Syrian people after children had just been gassed to death, he wasn’t going to help them, period. Teddy Roosevelt spoke softly and carried a big stick; Obama spoke like a schoolmarm and dropped his stick down a well. Once Obama let the red line be crossed without consequences, Assad knew there was no threat behind the president’s words — and a threat was the only thing that might cause Assad to back down. The war has gone on, but the Free Syrian Army basically doesn’t exist at this point; after years of waiting for America to live up to its promises — both figurative and literal — the people willing to fight against the Assad regime have joined up with whoever has the cash and weapons to protect them. (As choosing the wrong people to protect you can lead to death, people have predictably put their trust in groups sharing their own ethnicity and religion, turning a once broad-based rebellion into a completely sectarian war.) ISIS captured the Iraqi city of Mosul in June 2014, announcing its presence as actors on the global stage, and extremists in Syria have gotten more attention than Assad ever since — just as he planned it.

The greatest trick that Assad ever pulled was convincing people that moderate rebels didn’t exist. But they did. That so many people believe that the uprising’s slide toward extremism proves that Assad was right all along reveals a breathtaking lack of understanding and empathy. The Syrian people are being slaughtered by their own government. Entire cities — like Hama and Homs — have been reduced to rubble. Assad has been accused of using helicopters to drop barrel bombs — barrels filled with TNT and shrapnel — on civilian neighborhoods, and the pilot neither knows nor cares who the casualties will be. Journalists and doctors are deliberately targeted, like the British doctor who went to Syria on a humanitarian mission, was arrested by the government, and was killed in prison.

In some areas Assad’s forces have resorted to tactics straight out of the Middle Ages, laying siege to entire towns where rebels are holed up until they either surrender or starve to death. In 2015, according to a tally by the Syrian Network for Human Rights, the regime was responsible for 75 percent of all casualties in the conflict, and the vast majority of them were civilians.

My own family has been relatively spared because they live in Damascus, the capital, where Assad lives and his forces hold sway — but “relatively spared” is still relative. My wife, whose parents also hail from Damascus, has a cousin whose husband was arrested by the government two years ago. After months of bribing officials just to find out what happened to him, his family was finally put in touch with someone who knew, and casually told them, “Oh yeah, he’s dead.”

They don’t even know why — he wasn’t involved in the revolution at all. When my grandmother was on her deathbed a year ago, my mother was unable to visit her to say goodbye because of the risk that she’d be arrested by the government the minute she got off the plane — for the crime of writing critical things about Assad on Facebook.

And really, that’s small potatoes. My friends whose families hail from other cities in Syria, like Hama and Homs and Aleppo and Deir al-Zour, have all had close relatives killed — all by the Assad regime. One friend learned his cousin, her husband, and their three children were all killed by government gunfire. Their bodies were found huddled together in a corner in their apartment building.

If your own government did this to you, how would you respond? Imagine if President Trump — and if you like Trump, then President Obama — ordered the military into your neighborhood, and strafed your house with gunfire, and a sniper killed your daughter, and, after years of terror, you had to flee with nothing but the clothes on your back. Now imagine an extremist group — let’s call them the Westboro Baptist Church — showed up with guns, and anti-aircraft Stingers, and offered you cash to join them, and in return all you’ve got to do is hold up this “God Hates Fags” sign. What would you do?

Today, Syria is a nation in name only. Outside of the capital of Damascus, where the regime is headquartered and has its most support, the country is a wasteland. Aleppo, a city with a prewar population of 2.3 million, is in tatters today after Assad’s forces — with a big assist from Putin and Russia, undermining Obama’s decision not to intercede — destroyed half of it while reconquering it from the moderate rebels last month. Meanwhile, ISIS and other extremist groups continue to hold territory and rule over hundreds of thousands of people — while Assad, of course, has never targeted them.

No change in the facts on the ground has changed his opinion that he did the right thing. Obama has portrayed himself as a thoughtful, pragmatic executive in his eight years in the Oval Office, in contrast to the man he succeeded — but his stubbornness in refusing to admit that he screwed up in Syria even as the fire burns out of control is as ideological as anything George W. Bush did. When Elie Wiesel — Holocaust survivor, Nobel laureate, author of Night — died last summer, Obama eulogized him with the words, “We must never be bystanders to injustice or indifferent to suffering. Just imagine the peace and justice that would be possible in our world if we all lived a little more like Elie Wiesel.” The hypocrisy is breathtaking.

Call me naive if you want. The steady diet of World War II movies my dad made me watch with him as a kid made the Holocaust a very real and relevant event in my life, and made me hyperattuned to man’s capacity for evil when power is left unchecked. I took “Never Again” to heart. As an idealistic teenager I was appalled when America and the world stayed on the sideline while at least 800,000 Tutsis were slaughtered in Rwanda in the span of barely three months in 1994, and enraged when between 7,000 and 8,000 Bosnian men and boys were marched out of Srebrenica a year later under the noses of U.N. peacekeepers and mowed down by machine guns.

In 1998, while still president, Bill Clinton visited Rwanda and acknowledged that America and the rest of the world had been wrong to not intervene there four years earlier, an intervention that he admitted could have saved hundreds of thousands of lives. Years later he would call the decision not to stop the killings in Rwanda “one of my great regrets in foreign policy.” And the genocide in Srebrenica finally provoked the United States, with NATO backing, to launch air strikes on Bosnian Serb forces to prevent further massacres and bring them to the negotiating table.

This military action was an unquestioned success; the Dayton Peace Agreement ended the Bosnian war less than six months later, and eventually Serbian leaders Slobodan Milosevic, Radovan Karadzic, and Ratko Mladic were arrested and sent to The Hague on war crimes charges.

Bosnia and Syria are not perfectly comparable, but to the extent that they are, the fact remains that a focused military campaign in Bosnia worked to save civilian lives, and while the country is not exactly a tourist paradise today, the peace has held for more than 20 years. Through the air campaign and then having peacekeeping forces on the ground in Bosnia for nearly a decade afterward, America had exactly one soldier die in combat there. Bill Clinton was able to acknowledge he made a mistake by doing nothing in Rwanda. President Obama, while admitting in September that the Syrian war “haunts me constantly,” refused to concede that he should have handled the crisis differently, saying of a military response, “All those things I tend to be skeptical about.”

With the memory of the consequences of his actions in Bosnia and his inactions in Rwanda still fresh, Bill Clinton said this about Syria just months before Obama let Assad cross the red line: “If you refuse to act and you cause a calamity, the one thing you cannot say when all the eggs have been broken is, ‘Oh my god, two years ago there was a poll that said 80 percent of you were against it.’ You look like a total fool.” Clinton was wrong about one thing: Only 50 percent of Americans were against it. He was right about everything else.

In 2003, Samantha Power won the Pulitzer Prize for her book on America’s capability and responsibility to prevent further atrocities — A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide. Power joined then-Senator Obama’s presidential campaign as a foreign policy adviser in 2008, then joined his administration as part of the National Security Council, and since 2013 has served as the American ambassador to the United Nations. Despite having the woman who wrote the book on why America should use its power to prevent a situation exactly like Syria, Obama has done nothing to prevent it.

Power has stayed on in Obama’s administration, but Ambassador Ford — someone who understood Syria intimately — has not. He resigned his post, saying, “I was no longer in a position where I felt I could defend the American policy.” Ford understood what the Assad regime is, how impervious it is to things like “negotiations” and “compromise” and “civil rights,” and understood that there are some regimes with which you simply cannot negotiate. War is diplomacy by other means; when every other diplomatic measure has failed, sometimes it becomes necessary.

I see two main arguments that people use against military intervention in Syria. The first is to point out what happened in Libya. While no two conflicts are identical, there are parallels between the two countries; in both Libya and Syria, ordinary people rose up in protest against an authoritarian ruler in 2011, and in both countries, said ruler was willing to kill as many people as it took to maintain his power. But with Moammar Gadhafi’s forces en route to crush demonstrations against him by force, the United States led a NATO operation against the Libyan army from the air, and enforced a no-fly zone for seven months until Gadhafi himself was captured and killed.

America and the West then did what it usually does when the fighting is won, and ignored Libya’s need for an actual government to replace Gadhafi. In 2014, another civil war broke out. Today, Libya is a chaotic mess.

But it’s in far better shape than Syria is.

Perhaps the most important concept in sports analytics is “replacement level.” One can’t evaluate the value of a player simply by looking at his production on the field, but rather by comparing his production to what a likely replacement would do. A player who is below average is still valuable if the guy who would replace him is likely to be worse.

This analogy can extend to policy decisions. You can’t evaluate the decision to use military intervention in Libya without evaluating what the replacement option — not intervening in Libya — would have done. Critics of the decision to prevent Gadhafi from murdering his people will point out that thousands of people have been killed in Libya since protests began six years ago.

This is undeniably true. But to pin that on intervention is to imply that if there hadn’t been an intervention, few people would have died. That is clearly not the case, and the proof of that is the death toll in Syria, where we did not intervene — and the death toll is half a million and climbing.

This is not an apples-to-apples comparison; Syria is a nation defined by its cities, with roughly four times the population of Libya. But to look at what’s happened in Libya after intervention, and what’s happened in Syria after nonintervention, it’s not unreasonable to conclude that intervention saved lives.

You know who agrees with me? President Obama. In an interview with The New York Times in 2014, Obama defended his decision to prevent Gadhafi from slaughtering his own people: “I’ll give you an example of a lesson I had to learn that still has ramifications to this day,” said Obama. “And that is our participation in the coalition that overthrew Gadhafi in Libya. I absolutely believed that it was the right thing to do. … Had we not intervened, it’s likely that Libya would be Syria. … And so there would be more death, more disruption, more destruction.”

Had we not intervened, it’s likely that Libya would be Syria. This, from the president, is a paradox of thought.

The second argument against intervening in Syria is simply that America should not be the world’s police force, that we have neither the authority nor the right to interfere with other countries’ sovereignty, that it’s up to the rest of the civilized world to do its share. To which I reply: congratulations. You’ve gotten exactly what you wish for. We now live in a world where the United States doesn’t play peacekeeper. We now live in a world in which the United States lets other powerful countries, like Russia, police the world. That same world is the one that has given us a terrorist state the size of West Virginia, where 5 million Syrians have fled their country, where Europe is beset by a refugee crisis, and where Russia and Putin’s definition of “peacekeeping” includes helping Assad obliterate half of Aleppo.

If you still think that it would have been wrong for America to get militarily involved in Syria, then I have bad news: America is still militarily involved in Syria. It’s just that our involvement is against ISIS — a group that came to power in Syria only as a reaction to Assad’s brutality — instead. We’re still dropping bombs, and launching missiles, and even sending in special forces — we’ve got boots on the ground in Syria, when not even the rebels who were begging for our assistance five years ago were asking for boots on the ground. We’re still inevitably responsible for some civilian casualties. We dropped more bombs in Syria in 2016 than we did in any other country, in fact. It’s just that instead of using military force to remove a dictator from power, we’re using that force to keep him in power, by using it against the one group more noxious than he is — a group that he deliberately helped promote, and against which he has rarely targeted his forces, for precisely this reason.

Meanwhile, America continues to sell weapons to the Saudi government — including, reportedly, white phosphorus, a weapon so indiscriminate in its deadliness that its battlefield use is harshly restricted by law — to help the Saudis wage an indiscriminate war against rebels in Yemen that has killed thousands of civilians. If only Obama were as reluctant to allow American weaponry to be used to target civilians in Yemen as to protect civilians in Syria. Not to mention the civilians directly killed as collateral damage by American drone strikes in Pakistan and elsewhere.

In addition to being a moral disaster, and a geopolitical disaster, you could also argue that it has been a national political disaster for Obama and the left. The refugee crisis that has spiraled out of control has brought out the worst impulses of fear and xenophobia in Europe and in America. Brexit and the election of Donald Trump as president — the two most resounding defeats of liberal ideology this decade, if not this century — both came to pass by tiny margins at the polls. To the extent that unease over foreigners — remember, Trump made headlines for calling for a complete ban of not just Syrian refugees, but all Muslims entering the country — pushed even a small fraction of people to support Brexit or Trump, a case can be made that neither would have come to pass if Syria hadn’t spiraled out of control.

This choice made by the president has had a cascading effect, and the world has changed. In the years since, Syria has witnessed half a million people die and millions more flee their homes, Russia has risen on the world stage, white nationalist parties have gained power across Europe, anti-immigrant sentiment has flourished, the Democratic Party has been kneecapped, and his legacy has been debased.

Given that, as secretary of state, Hillary Clinton wanted more support for Syrian rebels, I had hopes that she might steer American foreign policy in the right direction there as president. Instead, President-elect Trump’s overarching foreign policy seems to be to buddy up to Putin, which is about the best possible news to hear if you’re Bashar al-Assad, and about the worst possible news to hear if you’re anyone else in Syria.

Then again, on Monday even Trump — in the process of criticizing German leader Angela Merkel for taking in so many Syrian refugees — argued that the West should have created safe zones in Syria. Criticism of Obama’s hands-off policy can be found everywhere — from the left, from the center, from the right, and even (at least behind closed doors) from John Kerry, his own secretary of state.

What happens in Syria going forward was probably a fait accompli before Trump was to take office. There is no light at the end of the tunnel. There is no foreseeable end to the killing, or to the refugee camps where a lost generation of children deprived of both education and hope is a bonanza for terrorist recruitment, or to the continued migration of refugees into Europe and Canada (but not, unless Trump changes his mind, America). There is no future there.

There is only the same dictatorship that has ruled for nearly 50 years, and has just proved that it would rather burn the country to the ground than give up power.

Rahm Emanuel, President Obama’s onetime chief of staff, once famously said, “You never want a serious crisis to go to waste.” Emanuel may be a terrible mayor, but he was right. The crisis in Libya, and Bosnia before it, came at a great human cost, but at least they weren’t completely wasted — at the end of them, the people who had instigated the crises were gone. But in Syria, the crisis — the greatest crisis of our time — has been completely wasted. It’s not just that hundreds of thousands of people have died — it’s that they have died in vain.

There is a cliché that goes, “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing.”

I want to believe that Obama is a good man. But he did nothing. A nation is destroyed. A people have been killed or scattered to the four winds. America’s authority on the world stage has diminished, and her moral authority has diminished even more. An unprecedented refugee crisis has upended Western politics. The only constant is that the Assad family still has an iron grip on Syria. Evil has triumphed.

President Obama did a lot of good in his eight years in office. But it’s what he didn’t do that I’ll always remember. I never want to see his legacy discussed without mention of the decision that will forever stain it.

And I never again want to hear “Never Again.”

Comments About This Article

Please fill the fields below.