The Global Peace Index for 2013 shows how world peace has changed over time - unsurprisingly, the violent conflict in Syria has had a big impact on the findings

The world has become a less peaceful place according to the Institute for Economics and Peace. In their annual report, the Global Peace Index, they rank 162 countries by measuring security in society, the extent of conflict and the degree of militarisation. This year's report reinforces a longer term pattern they have noted: since 2008 levels of peace have fallen by 5%.

Their findings are not altogether bleak. While the number and intensity of internal conflicts has risen in recent years, hostility between states has fallen. Overall, they found that 110 states have become less peaceful and that 48 have become more so.

Despite financial turmoil of recent years, Iceland has topped the list, thanks largely to its political stability, low homicide rate and small prison population. The top of the list was littered with Western European nations that have long been peaceful; Denmark, Austria, Switzerland, Finland, Sweden and Belgium all made it to the top 10. In 6th place, with stringent laws on possession of firearms and good neighbourly relations, is Japan.

At the other extreme, Afghanistan continues to languish in 162nd position despite the drop in the number of people killed as a result of internal conflict, refugees and displaced people. The country fared particularly badly on the 'political terror scale' - an indicator that uses Amnesty International and the US Department of State's Country Reports on Human Rights Practices to evaluate levels of political violence and terror.

Somalia narrowly beat Syria to 161st place in this year's table. Other countries that were considered amongst the most violent and unstable were Iraq, Sudan, Pakistan and, less frequently cited, Russia. Several of these countries were also characterised by high levels of bloodshed within their territories.

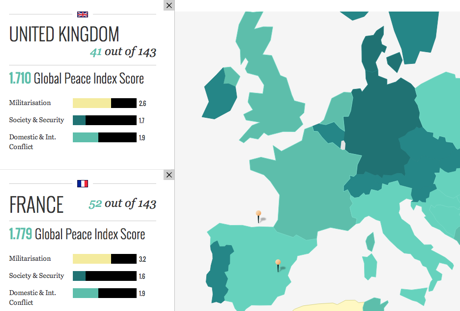

Image: Institute for Economics and Peace

Image: Institute for Economics and PeaceMost changed

This year is the seventh that the Global Peace Index have published this analysis, and Syria stands apart as the most radically changed country during that time with a score that has plummeted by 70% since 2008. Côte d'Ivoire which has experienced heightened violence since its president was ousted from power, as well as Burkina Faso, where the army has gone on a series of destructive rampages, are two other countries that have seen severe deteriorations in peacefulness.

Meanwhile, Libya has moved up three places in the global rankings as the tumult of the revolution is beginning to subside. Chad also continues to witness improvements after the end of its civil war in 2010, and has moved up four places as a result.

Image: Institute for Economics and Peace. Click to use the Global Peace Index interactive map

Image: Institute for Economics and Peace. Click to use the Global Peace Index interactive mapMethodology

In an attempt to draw together the multitude of valuable studies on global violence, the Institute for Economics and Peace has used a wide-ranging definition. This includes both positive measures of peace (institutional capacity and resilience) as well as negative peace, famously defined by Johan Galtung as 'the absence of violence or fear of violence'.

Countries are given scores on 22 indicators that measure internal peace (e.g. levels of perceived criminality, number of police per 100,000 people and level of organised crime) as well as external peace indicators (these include military expenditure as a % of GDP and nuclear weapons capabilities).

Looking at this micro-level of data, important international changes emerge. For example, over the past five years UN peacekeeping contributions have increased and the number of homicides per 100,000 people has fallen dramatically. However small arms and light weapons have become more accessible and the capability of nuclear and heavy weapons has continued to grow, suggesting that many countries remain unwilling to demilitarise.

Cost of conflict

The report also counts the cost of violence to the global economy - and the sums are far from trivial. They estimate that the economic impact of containing violence cost $9.46 trillion in 2012, equivalent to 11% of global GDP.

The report adds:

Were the world to reduce its expenditure on violence by approximately 50 per cent it could repay the debt of the developing world ($4076bn), provide enough money for the European stability mechanism, ($900bn) and fund the additional amount required to achieve the annual cost of the Millennium Development Goals.

It seems that while patterns of peace continue to shift around the world, the key trend is one where the biggest threats exist within, rather than outside, a country's borders. Despite that, most countries appear unwilling to relinquish their capabilities to combat violence from abroad.

See this year's rankings and scores below. There's a link below to data for each of the previous years so you can explore changes for each country.

Comments About This Article

Please fill the fields below.