Last summer Rida, a 29-year-old father of three from Syria, decided it was time to cross the border from Lebanon and head back home. His native city of Homs had been devastated during Syria’s civil war, but seven years after he fled it was back under the control of forces loyal to President Bashar al-Assad.

By October, he still felt he had made the right choice in returning. “People are working and living their life normally,” he said at the time, adding that he felt relatively safe.

But nearly a year on, Rida carries a gun, wears army fatigues and is far from Homs. He no longer thinks leaving Lebanon was wise.

Soon after his return he was conscripted as an army reserve and sent hundreds of miles from Homs to the Damascus countryside — formerly an opposition stronghold, where entire neighbourhoods have been levelled by Russian and Syrian air strikes.

Meanwhile, in Homs, “others are taking over”, he said. “The corruption is unbearable . . . Those who have connections are doing well, everyone else has to shut up and endure injustice in silence or face detention.”

Syria’s bitter eight-year civil war is grinding to a halt. Fighting still rages in the last opposition-held pocket of the north-west but Mr Assad’s authoritarian regime has regained control over about two-thirds of the country since 2018, helped by the firepower of allies Russia and Iran.

Mr Assad has urged refugees to return, accusing host countries of “[holding] on to the refugee issue with their nails and teeth” to take advantage of foreign aid.

Yet of the 5.6m Syrians who fled the violence, only about 3 per cent — 170,000 people — have returned since 2016, UN records show.

Already deterred by shattered infrastructure and a moribund economy, refugees also say they are worried about military conscription, random arrests and a climate of fear.

Their reluctance to return is also a problem for Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan, which have taken in the largest number of those fleeing Syria.

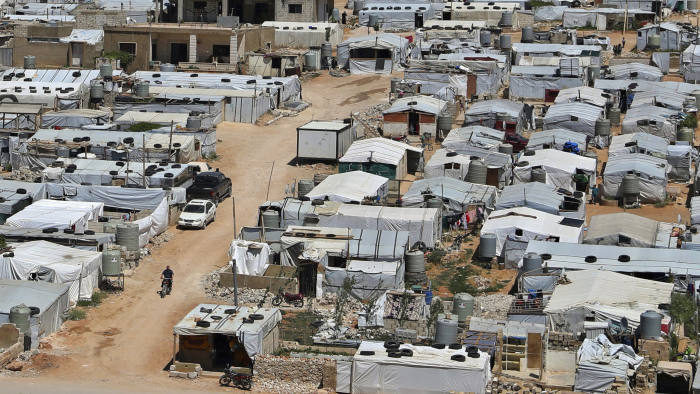

Donor countries have spent billions on aid to the three countries, hoping to avert a repeat of the 2015-16 migration wave into Europe that has stoked destabilising rightwing populism. But the host countries complain that the inflow — they have taken 5.2m refugees between them — has badly stretched their infrastructure and that anti-Syrian sentiment is building. In some areas, the refugees are facing increasing hostility from the authorities themselves and pressure to go home.

But exiled Syrian men say going home would mean either risking death in the military or disappearing into the country’s vast prison network. Human rights groups have documented widespread torture and abuse of detainees.

Rida said the worst thing about the Syria that he has returned to was the paranoid atmosphere, suffused with anxiety that a malicious neighbour might inform on him. “If someone is annoyed with you, they write a report to the intelligence and then you will disappear,” he said. “You will not reappear without a thousand connections.”

International human rights groups say tracing returnees inside Syria is difficult — Sahar Mandour, an Amnesty International researcher, described it as a “black hole”. But the locally based Syrian Network for Human Rights estimates that almost 2,000 returning Syrians were detained between 2017 and 2019.

With the regime aiming to strengthen its grip on retaken territories and assert its dominance in areas that never fell to the opposition, analysts say security apparatus reform is unlikely.

That means “Syria is not safe at all” for those who “left Syria because they were scared of getting arrested or [of] enforced disappearance”, said Noura Ghazi, director of Nophotozone, a non-governmental organisation that supports the families of detainees.

Yara, a 52-year-old refugee living in a tent in north Lebanon, has reason to fear the state. Her teenage son was arrested when he entered Syria seeking cheaper medical treatment in 2014. He has been detained for five years.

According to his family, his crime was affiliation with a regime traitor: Yara’s brother was a military commander who had defected. The family fled Syria in 2013 after Yara was detained and questioned by security forces.

“They tortured people in front of me so I would tell on my brother,” said Yara, who said she believed she was spared physical abuse because another relative is a high-ranking military official.

She is convinced the regime is holding her son and three other relatives to put pressure on the defector to turn himself in.

Although Yara has a heart condition and is sinking into debt after cuts to aid, she will not consider going back. “My name is already on the list,” she said. “Do you think that person would dare to return?”

Syrians face other threats in areas where open warfare has ended, said Sara Kayyali, Syria researcher at Human Rights Watch. These include militias harassing and extorting civilians at checkpoints and local authorities with control over who is allowed to move back to their area.

Rights groups fear European countries are nonetheless moving to consider Syria ready for return. Denmark has reclassified Damascus as safe, affecting residency for asylum seekers originally from the Syrian capital.

Even when refugees do try to go back, the regime does not accept everyone, with those intending to leave Lebanon first vetted by Syrian security authorities.

Rida insisted he did not regret going home but admitted life was easier in Lebanon. There, he said, “I had no problems with the authorities”.

Financial Times

Comments About This Article

Please fill the fields below.