Despite many attempts at negotiations, the Syrian war – a conflict with a complicated and constantly changing cast of characters that has killed as many as 585,000 people and displaced over half of Syria’s prewar population – has proved extremely difficult to resolve.

As the war grinds on, conditions are only getting worse. For months, the Syrian regime and its Russian allies have been engaged in an assault on Idlib, the last rebel-held region in the country. That has sparked an exodus of nearly a million people toward the now-sealed Turkish border. Although the U.N. has tried to deliver badly needed relief, many Syrians are facing winter conditions without shelter and there are reports of children freezing to death.

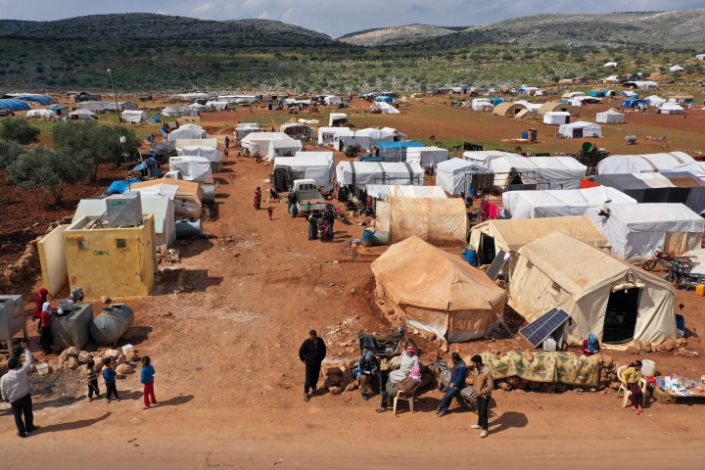

On top of all this, Syrians are now facing the coronavirus outbreak, which poses a devastating threat to the displacement camps jammed with people fleeing the conflict, who have no opportunity to practice social distancing – or even wash their hands.

I am currently working on a book about the war in Syria. The Syrians I’ve spoken with in the course of my research point to many reasons for their country’s tragedy. For many of those I spoke with, those reasons include the Assad regime itself and, for at least some, the rebels as well.

But there are two factors that stand out in explaining why the war seems to be so intractable and peace so sadly elusive: First, everyone in Syria is fighting a slightly different war from everyone else. And second, the war involves lots of outside participants, all with their own goals.

With a fast-spreading dangerous disease on the doorstep, the situation in Syria looks grimmer than ever.

A complex mix of battles and wars

The Syrian war involves a sometimes bewildering constellation of participants.

At a bare minimum, they include President Bashar al Assad’s regime; the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) and its associated armed wings (the YPG and YPJ); the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, or IS; and the constantly shifting array of armed groups who make up “the opposition” (sometimes also referred to as “the rebels”), which have included everyone from former army officers, to foreign jihadists, to local warlords.

Each group has its own objectives. The rebels and the regime seek control of Syria itself. In contrast, the Kurds and the Islamic State group were (and are) fighting to carve out entirely new territories with new boundaries and new forms of government. These conflicting objectives mean that what might appear from the outside as a single war is really a collection of semi-related subconflicts.

By 2012, the nonviolent uprising against the Assad regime the had begun in the spring of 2011 had morphed into a military conflict between the regime and a range of rebel groups. While all of the rebels were bent on removing Assad from power, they often had quite divergent visions of what or who might replace him (although in most cases, the answer was “themselves”).

Beginning in mid-2013, fighting erupted in the north between the Kurdish armed groups and the Islamic State group, a conflict that was largely disconnected from the war being waged elsewhere in the country. In 2018, Turkish-sponsored rebel groups attacked Kurdish territory in the north, while other rebel factions continued fighting the regime – and still others fought amongst themselves.

All this infighting and complexity means that even if a settlement is reached that satisfies some groups, it is unlikely to satisfy everyone. There will almost certainly be someone left with an incentive to keep fighting.

Major international forces are involved

Nearly every one of these factions has support from foreign allies. The Assad regime is backed by Russia, Iran and the Iran-backed Lebanese armed group Hezbollah.

The various rebel factions each have their own backers, including Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar.

The Kurds have received U.S. military support in their campaign against the Islamic State group – which has the dubious distinction of being so unpleasant that no nation is willing to openly support it.

This outside support has enabled all the war’s participants to keep fighting for far longer than would have been possible without it. In particular, direct Russian intervention in 2015 probably saved the Assad regime.

At the same time, all of these foreign parties are in Syria for their own interests. Russia hopes to preserve both its influence in the region and access to its naval base in the Syrian city of Tartus.

Turkey seeks to prevent the Syrian Kurds from establishing their own autonomous territory on its southern border, fearing this would work to the advantage of the PKK, the Kurdish armed group that has been embroiled in a conflict with the Turkish state since the 1980s. Aside from some early support for some parts of the opposition, the U.S. has mostly focused on containing the Islamic State group.

All have engaged in military strikes that have cost Syrian lives, including Turkish attacks on Afrin, the American bombardment of Raqqa and Russia’s assault on civilian targets across Syria.

From bad to worse?

Recent developments suggest that, if anything, the situation in Syria is worsening. Most of the war’s participants, including (and recently, especially) Assad’s regime, have attacked medical facilities, humanitarian aid operations and refugee camps.

One new factor stands to significantly complicate the situation in Syria: If there is an outbreak of the novel coronavirus and its associated disease, COVID-19, anywhere in Syria, the results will be catastrophic. The Syrian regime has acknowledged nine cases and one death so far, though the number may well be higher. Given the poor state of the country’s health system, things will likely get much worse.

Displacement camps in Syria and refugee camps outside of Syria provide ideal conditions for the spread of disease. With much of the country’s medical infrastructure and equipment damaged or destroyed, especially outside of Damascus, treatment will be extremely difficult.

The Assad regime may be close to winning a bitter victory. But the country’s future doesn’t look good.

For one thing, an end to the war doesn’t necessarily mean an immediate cessation of all violence; opposition forces may wage a low-grade insurgency for years to come, as has happened in Iraq.

Even if violence does end, rebuilding Syria will require an enormous amount of money and human effort – both of which are in short supply there. Many of the Syrians who fled in the war’s early years were young and educated – exactly the people whose skills Syria will desperately need in order to recover. But they may not be willing to return, either out of fear of reprisals from the regime, or because they have nothing to return to.

The process of rebuilding Syria will be further hampered by the regime itself; the corruption and repression that protesters objected to in 2011 remain very much a part of Assad’s government. Amnesty International has documented the use of torture against tens of thousands of Syrians, especially in the notorious Sadnaya Prison.

Probably unsurprisingly, few of the Syrians I have interviewed expressed much admiration for or confidence in any of the participants in the war – neither for the various nonstate armed groups involved, nor for the regime. As complex as ending the Syrian war has proved, building the Syrian peace may prove to be almost as difficult.

The Conversation

Comments About This Article

Please fill the fields below.