he last time Syria held presidential elections, in 2014, there was no question over whether President Bashar al-Assad would win – but with opposition forces in control of the country’s cities, as well as the suburbs of Damascus, his future was still far from certain.

Seven years later, after the regime’s Russian and Iranian allies intervened and turned the tide of the war, most of Syria is now back under Assad’s grip. On Wednesday, his citizens will return to the polling booths for a sham democratic display designed to give the president a veneer of legitimacy both at home and abroad.

“In 2014 the mood was different. Assad could still have gone. Now Syrians still in the country, and all of us who left, know that there will not be a military overthrow,” said Suhail al-Ghazi, a Syrian researcher and non-resident fellow at the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy.

“The elections will be used by both the regime and Russia to show that they won, and they claim Syria is safe, so refugees can return. The election is also a factor in rehabilitating the regime among Arab countries, and maybe the Arab League.”

Syria has been ruled by the Assad family since 1970, after which the parliament and government were stripped of many decision-making powers and important positions filled with loyalists as the Ba’ath party worked to consolidate its status as “leader of the state and society”.

Bashar was the third choice as successor of his father, Hafez, taking over after the latter’s death in 2000. The mild-mannered ophthalmologist claimed he wanted to bring genuine political reform to the country, but ended up inflicting even more brutality than his father. Street protests during the Arab spring in 2011 were met with extreme violence from the police state and spiralled into a complex and intractable civil war.

In the early days of the uprising, large numbers of military and party officials defected in protest at the government crackdown. As the level of dissent across Syria’s stratified society began to make itself felt, the emboldened opposition boycotted parliamentary elections which took place in 2013.

A hollow attempt at mollifying public opinion was made in 2014’s presidential elections, when the regime allowed multiparty elections for the first time – but Assad unsurprisingly still won nearly 90% of the vote after a campaign in which one of the opposition candidates told voters the incumbent should remain president.

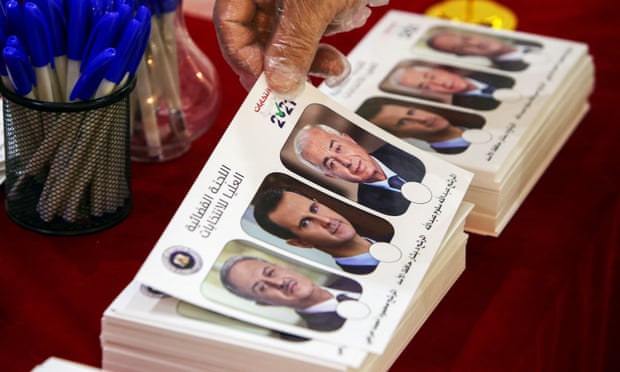

This year’s campaigning began after the supreme constitutional court approved three out of 51 candidate applications a week ago: Abdullah Salloum Abdullah, a former member of Syria’s legislative authority; Mahmoud Ahmad Marie, who is part of UN-sponsored peace talks in Geneva; and Assad himself.

While Assad is sure to win a fourth seven-year term, all three candidates have pledged to repair the economy, which collapsed last year under the weight of war, sanctions and Covid-19, and bring the country’s five million refugees home. Abdullah also made a bold promise to tackle corruption, which is systemic in Syria.

An amnesty earlier this month for more than 400 civil servants, judges, lawyers and journalists detained in a crackdown on social media dissent has been widely viewed by rights activists and the loved ones of tens of thousands of detainees still missing in regime prisons as lip-service to democratic norms before the poll.

“My brother disappeared into a regime prison in 2013. We still have no idea if he is alive or dead. They won’t give us any information,” said Saed Eido, originally from Aleppo but now living in the Turkish city of Gaziantep. “All this presidential election does is whitewash crimes and maintain a dictatorship.”

Ghazi agrees: for the regime, he said, the election is a useful propaganda tool. “The regime has always made people do this to prove their loyalty. Marching in parades, waving banners, turning up in large numbers to vote … For the new generation it’s also a chance to create a sense of community and nationhood.

“Today’s young people in Syria have never experienced any political activity that is not linked to armed activity. It’s a break from their terrible reality, almost, a way for the regime to make them feel included, bring them into the system, make them feel like they belong.”

A crash in the value of the Syrian pound in early 2020 means that around 90% of people living in regime-controlled areas are now living in deep poverty. Public criticism of deteriorating living conditions is not tolerated, but even so, the situation has triggered unrest in areas of Syria where the regime’s grip is more tenuous. In Druze-majority Sweida, in the south-west, election billboards erected last week were torn and splashed with red paint within hours.

The elections also blackball years of UN-backed efforts aimed at ending the war, including forming a transitional governing body and rewriting the Syrian constitution in order to hold free and fair elections subject to international monitoring.

“Many civilisations, invaders and colonisers have passed through Syria. But today they are just remnants of the past and historical sites,” said Eido. “The regime is not there to rule, just to steal the livelihoods of its own people. That’s why, like the others, it won’t last. It can’t sustain itself for ever.”

By Bethan McKernan, Middle East correspondent

The Guardian

Comments About This Article

Please fill the fields below.