Syrian theater was never born of a moment of infatuation with the West or as an imitation of an imported art form. It has always been the rooted child of its environment, a living embodiment of the spirit of spectacle and celebration that has pulsed in the heart of this land for millennia. It is this very spirit that made Syria the cradle of Dionysian rites, fertile ground for the arts of the storyteller (al-hakawati) and shadow puppetry, and later the platform for the first modern Arab theater pioneered by Abu Khalil al-Qabbani. This article traces the genealogy of Syrian theater, not as a linear history of names and performances, but as an ongoing story of dialogue between the sacred and the profane, the ritualistic and the celebratory, the collective and the individual. Roots Deep in History and Intertwining Cultural Contexts The myth of Dionysus (Bacchus), the wandering god, forms the archetypal model for the idea of death and rebirth linked to the cycle of nature and agriculture. In the rites of the "Dionysia," worshippers would leave the cities for the mountains, where they would dance and sing in a state of ecstasy that unleashed instinct and dissolved the boundaries of the individual self into the crucible of the community. As Aristotle indicates in "Poetics," tragedy itself originated from the leaders of the dithyramb—that collective Dionysian hymn performed in a circle, accompanied by ecstatic dance and music. Syria was not merely on the periphery of this phenomenon but an active center. Breathtaking archaeological evidence attests to this, such as the Roman theater in Bosra with a capacity of fifteen thousand spectators, the "Dionysus" mosaic in Shahba depicting the god in his triumphal procession surrounded by his mythical entourage, and inscriptions and statues in Palmyra and Apamea dedicated to "Dionysus, god of wine and joy." The spirit of Dionysus interacted with older, more deeply rooted local rituals, like the rites of Adonis in Phoenicia and the Syrian coast, where women would plant rapidly withering "Gardens of Adonis" and then lament over them in a collective dramatic scene, and the rites of Astarte (Ishtar) in Palmyra and Harran, which involved processional dances and raucous music, all aimed at invoking creative and fertile powers. The Arts of Popular Spectacle: An Oral Memory and a Living Body In cafes, alleyways, and public squares, a different kind of "spectacle" was created, one needing no raised stage or entry tickets. In the "Al-Nawfara" café in Damascus, the hakawati (storyteller) would sit on his slightly elevated chair, with his prayer beads and cane, narrating the epics of heroes through a lively performance that transformed narration into drama and the listener into a partner in creating meaning, as noted by researcher Shaker Abdel Hamid. In popular cafes, the art of shadow puppetry (Karagoz and 'Aywaz) presented satirical dialogues with leather puppets that critically mocked the unjust ruler, the fraudulent merchant, and the hypocritical religious figure with biting symbolism, as in Karagoz's line: "Folks, the world has become strange... He who has no money, his words have no weight!"

In religious and Sufi spaces, like the Sulaymaniyya Takiyah in Damascus or Sufi lodges in Aleppo, the chants and the repetitive whirling of dervishes in their white robes created a state of collective ecstasy that transformed ritual into an aesthetic performance. In popular celebrations, the dabke dance expressed community cohesion through synchronized footwork, while the mawwal (traditional sung poem) condensed a complete tragedy of love and separation into a few minutes of poignant singing.

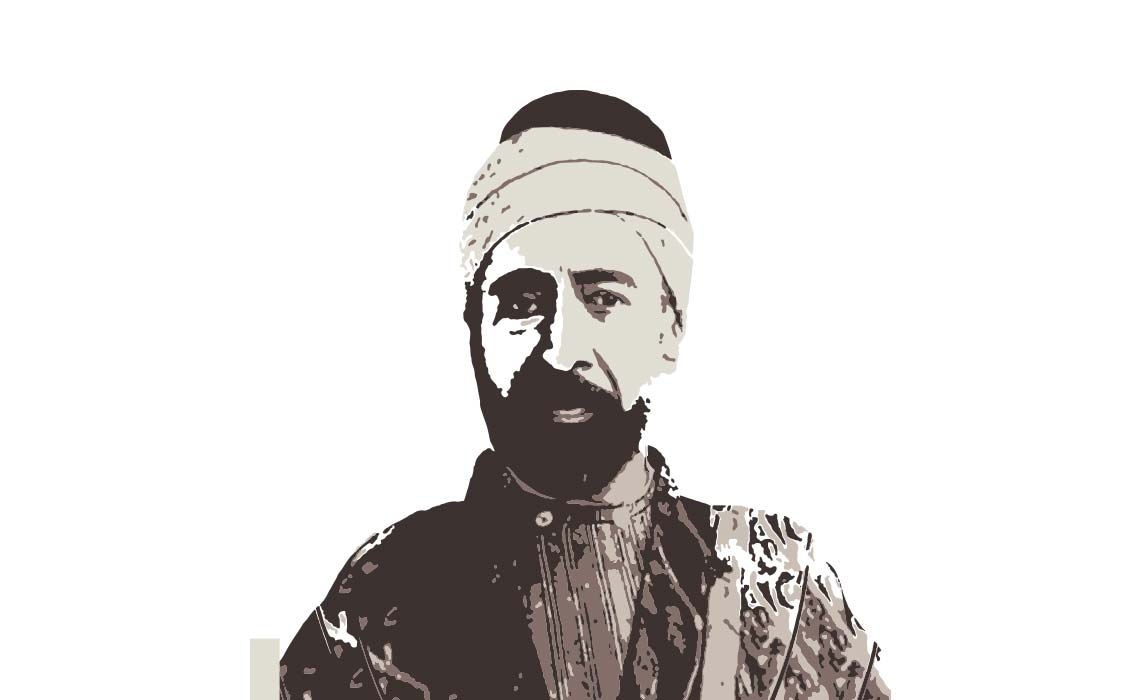

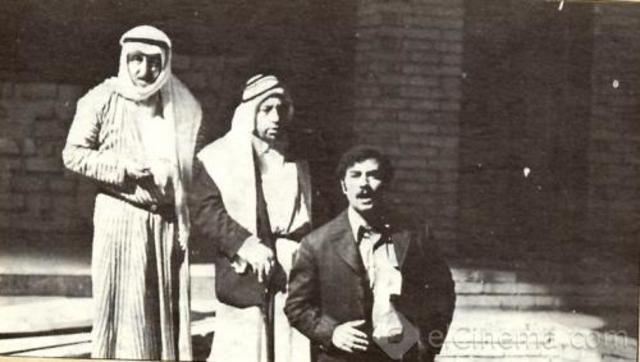

Abu Khalil al-Qabbani: The Moment of Founding and Transformation

Within this rich climate, modern theater was born in Damascus through the convergence of several factors: a unique cultural diversity, active commercial movement, a rich heritage of popular arts, and an intellectual elite gathering in literary salons.

From this environment emerged Ahmad Abu Khalil al-Qabbani (1841–1903), who grew up watching hakawati and shadow puppet performances but recognized the limitations of pure narrative form. He states in his memoirs: "I saw in the tales of the storyteller and the hakawati the seeds of a great theater, needing only someone to polish them."

Al-Qabbani presented his first independent theatrical performance in 1871 titled "Al-Sheikh Waddah, Misbah, and the Nourishment of Souls," combining music and singing (influenced by Sufi sama and mawlids), dramatic dialogue (evolved from the hakawati style), and choreographed dance (inspired by the dabke and folk dances), while preserving a spirit of improvisation and spontaneity. However, this innovation faced fierce resistance from conservative currents that saw his art as violating values, as stated in a petition submitted by religious scholars in 1883: "What this man does of acting, dancing, and mixing [of genders] contains many religious prohibitions, and it distracts people from the remembrance of God and from prayer..."

Twentieth-Century Theater: Between State, Identity, and Resistance

The first half of the twentieth century witnessed the transformation of Syrian theater into an artistic institution, with the state beginning to sponsor it as a tool for building national identity.

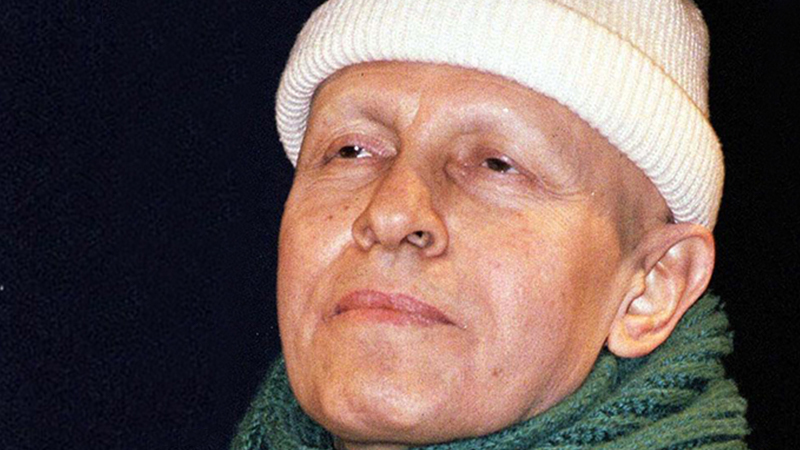

However, the shock of the 1967 defeat caused a radical shift, moving theater from glorifying historical heroism to criticizing the self and harsh reality. This was evident in the works of Saadallah Wannous, who in 1968 presented the play "Soirée for the Fifth of June," which broke theatrical illusion by using real news reports and turned the audience from passive spectators into partners in critical analysis.

This critical theater reached its peak with the play "The King is the King" (1977), which presented scathing criticism of the relationship between authority and the people through a story from heritage, using black comedy and the idea of "authority as theater." Within this climate, theatrical trends multiplied between experimental, street, university, and children's theater, enriching and sustaining a vibrant scene.

Twenty-First Century Transformations: From Crisis to Resilience

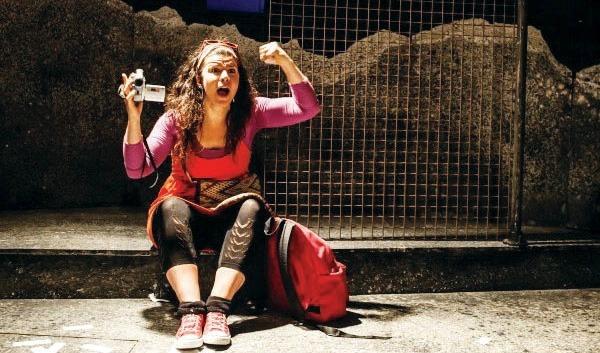

Prior to 2011, Syrian theater was experiencing relative prosperity with the establishment of the Damascus Theater Festival and the spread of experimental performances, but it also suffered from state bureaucracy, a crisis in playwriting, and competition from modern media. With the outbreak of the crisis, theater suddenly transformed into an art of resistance and a means of documentation, with performances held in people's homes, basements, and on balconies. Innovative forms emerged, such as mobile bus theater, digital theater via the internet, and documentary theater that recorded events in a dramatic language.

During this phase, the role of women in theater stood out, evolving from actresses in stereotypical roles to directors, writers, and leaders of independent troupes addressing women's and societal issues from new perspectives. New theatrical generations also formed: the generation of the crisis, concerned with survival and documentation; the generation of exile, carrying the concerns of belonging and memory in the diaspora; and the post-2018 generation, thinking about reconstruction and reconciliation.

Toward a Future that Carries Memory and Builds Bridges

Syrian theater, throughout its long journey, has proven a unique capacity for transformation and resilience, turning tragedies into creative energy, displacement into opportunities for dissemination, and painful memory into material for meaningful art. Today, it looks toward a phase of reconstruction by establishing documentation centers, developing "theater of reconciliation" that addresses the wounds of the past, adopting contemporary digital forms, and building bridges between theater inside Syria and in the diaspora.

Ultimately, Syrian theater remains an ongoing dialogue between past and present, individual and community, heritage and modernity, reality and dream. A dialogue that will not cease, because it resembles life itself in Syria—complex, difficult, sometimes painful, yet always worthy of being told, lived, and immortalized on the stage.

Mohamed Hamdan is a playwright and researcher in cultural studies and ancient Eastern heritage.

Comments About This Article

Please fill the fields below.