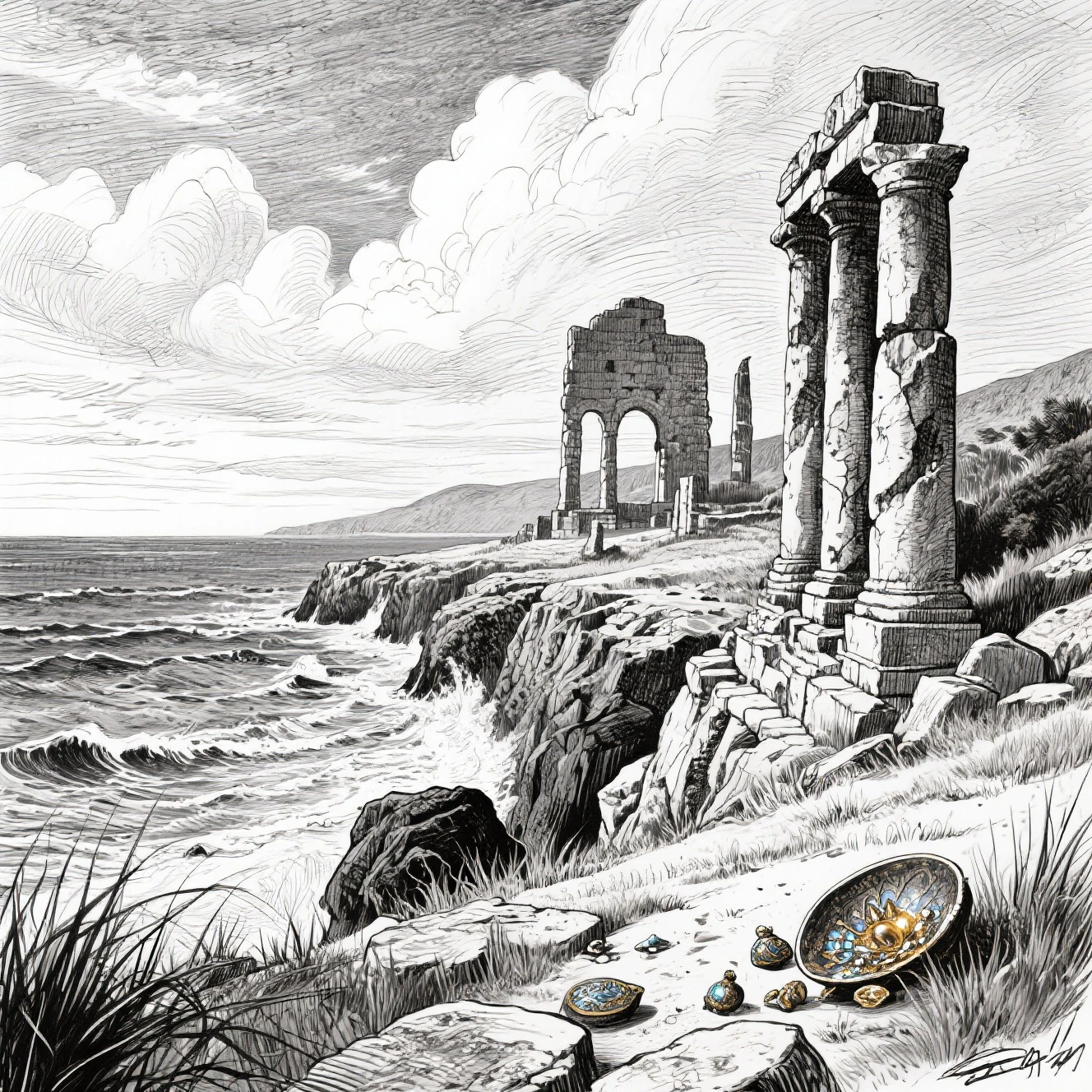

On the eastern shores of the Mediterranean, where majestic mountains meet an emerald sea, lies a land that is more than a mere geographical expanse—it is a mystical keeper of the spirit of place. Here, in this enchanting realm, the soil, hills, and rocks hold within them legendary tales carved over millennia. Beneath the green grass of every hill lie remnants of an ancient temple, and through every valley echoes the hymns once sung to gods of fertility and love.

A Treasure Hidden Beneath Ashes

At the heart of this sacred geography, the grapevine remains far more than just a plant—it is a living witness to an enduring dialogue between humanity and nature. Successive civilizations have revered it, from the Canaanites who saw its juice as the blood of the earth, to the Greeks who turned its wine into the drink of Dionysus, a bridge between the material and the spiritual. Wine was a ritual of the collective unconscious, a key to tranquility and connection with the transcendent.

To this day, the grapevine extends its deep roots into the culture of the Syrian coast's people as a living daily practice. It carries with it a heritage of resilient joy passed down through generations. This organic bond is what makes the coast a unique mosaic, where the humble farmer picking grapes today becomes the unspoken guardian of a millennia-old legend.

Yet this coast, bearer of such depth, which witnessed the genius of the Phoenicians and echoed with the tales of Bacchus in its ports, today lives a different reality, facing a stark historical paradox. It is a treasure hidden beneath ashes, torn between a grand civilizational legacy and immense potential on one side, and harsh economic and living challenges on the other.

It is a contradictory tableau: Crusader castles gaze from green hills over villages struggling for basic infrastructure, and golden beaches where the ships of Ugarit once docked stretch toward a sea that has known decades of isolation. Herein lies the painful irony: the land that sanctified the vine, fertility, and beauty finds itself today unable to transform this heritage into a lever for a dignified life for its children.

The challenges extend beyond a lack of investment to include crumbling infrastructure, international isolation, and the accumulation of war years that have shifted part of the community's energy from building to mere survival. Thus, blessing turns into a temporary burden, and myth into a sorrowful memory, unless the links between this glorious past and a present seeking hope are renewed.

But within this very contradiction lies the same seed that preserved the continuity of the vine through the ages: resilience. The coast that has withstood history today holds a unique opportunity to write the chapter of its renaissance not only with its resources but with the wisdom drawn from the depth of its experience. The hidden treasure is not only in the artifacts underground or the landscapes above, but in this coastal strip's potential to become a model of sustainable development that starts small, from the local community—from that very farmer who guards the legend.

The Weight of Memory and the Scars of Conflict

The beginning could be activating domestic tourism and encouraging small projects that preserve human dignity and the heritage of place, to eventually become a bridge reconnecting the coast not only to its prospering geographical neighbors but to its historical place in Mediterranean civilization, which has always been a blend of trade, art, and life. And so, the grape clusters may come to remind the world not only of the myths of the past but of the promise of a future that can revive that authentic Mediterranean joy anew.

Historical memory, with its load of past wounds and the burdens of conflict, has long formed a psychological barrier deepening the sense of isolation among the region's people. These are not merely bygone events but fragments that still embed themselves in the daily fabric, surfacing in the consciousness through grandmothers' tales and mapping themselves onto place names and the faces of stones in mountain villages. This dual memory—carrying the grandeur of a civilizational heritage on one hand, and accumulated pains of displacement, persecution, and political defeats on the other—has created a kind of existential caution. A wariness of the stranger, of change, of openness that might bring unforeseeable consequences. History has turned part of this coast into a psychological fortress, sheltering behind a wall of silence and withdrawal, fearing that fate might repeat its tragedies.

Amid this historical isolation came the long years of war, adding new layers of suffering and division. The coastal inhabitant, molded for joy and generosity, who learned from ancestors that the sea brings strangers sometimes as traders and friends, sometimes as invaders and occupiers, suddenly found himself at the heart of the storms. His alluring city turned into a safe haven overflowing with displaced people, multiplying the burdens on its infrastructure and social fabric. And he himself transformed, overnight, from a farmer tending his vine, a fisherman dreaming of the day's catch, or a student planning his future, into a number in an equation of a conflict larger than himself, or a survivor trying to grasp a thread in a scattered life.

Under the weight of this tempest, rituals of collective joy dwindled, the songs that once accompanied harvests and planting seasons receded, replaced by the preoccupation of daily survival. Yet what is striking is that the dream of stability and dignified living did not die; it remained like an ember beneath the ashes. It is not a luxury but a basic need, like air and water, for the people of this land. It is the same dream that drove his ancestors to cultivate the coast with fruitful trees despite all history's invasions: to have land from which to provide for his family, a home to shelter in, a future to bequeath to his children without fear. It is the yearning for an ordinary, simple life where he can sip his coffee on a balcony overlooking the sea he loves, not as a barrier crossed by desperate refugees, but as a horizon open to possibilities and beauty.

This contradiction between historical strength and present fragility, between mountainous withdrawal and the call of the open sea, is what creates both tragedy and opportunity in the Syrian coast today. Its ancient cultural memory may be a burden weighing on its steps, but it is also an invaluable treasure if used as a bridge for understanding and dialogue, not as a wall for isolation. And the dream of its people for stability, if it finds a listening ear and a real opportunity, could be the strongest engine for reconnecting this weary land to its deep roots of generosity, creativity, and joy, propelling it toward a destiny different from the one drawn for it by the conflicts of past and present.

How Instagram and Humble Hospitality Are Forging a New Path

But hope, like a climbing plant that grows in the cracks of rocks, always searches for a crevice. And this crevice has begun to appear from where many do not expect. Recently, the cameras of "nomadic influencers" and the footsteps of tourists have ceased to be mere passing images, transforming into open windows onto a world that was closed. These lenses have done what promotional campaigns failed to do for decades; they did not just show stunning landscapes but conveyed the human moment—a family's laughter by the White River beach, a young man's awe before the Roman arches of "Amrit," the warmth of a village's hospitality in receiving a foreign guest.

This visual revelation had a dual effect: On one hand, it gave Syrians themselves a different image of their coast, an image not marred by war or obscured by daily life's worries. How many youths from inland Syria had not known that just hours away lie green forests touching the sea, or wondrous caves like those in "Ain al-Tineh." On the other hand, it offered the outside world—especially the Arab neighborhood—an implicit message: "Life here has not stopped, and beauty is capable of endurance."

Domestic and Gulf tourism have indeed flung the door wide open to a spontaneous yet profoundly impactful economic movement. It is no longer confined to large hotels but has materialized in the simplest manifestations of life: the young man who turned his small car into a "mobile kiosk" selling coffee and drinks on mountain roads, or the family that began receiving guests in their simple rural home, offering them breakfast from their own land and olives. This movement, though simple, is changing entrenched economic perceptions; it proves that tourism can be a direct and tangible source of livelihood, not some distant government project.

More importantly, these flashes of tourism have given a realistic glimpse of immense potential. The idea of transforming the region into a genuine tourist destination is no longer a rosy dream but a living project whose initial results are felt by every family that has paid off a debt, started a small business, or sent a son to university with the earnings from selling breakfasts to visitors. It is tourism from which the simple person benefits before the big investor, making it more sustainable and deeply rooted in the community.

Here, a beautiful contradiction emerges: while historical memory bears the wounds of isolation, the stranger today comes bearing seeds of communication and hope. While the land was for centuries a theater of conflict, it becomes today an arena for hospitality and encounter. It is a subtle yet profound shift, indicating that the coast's future may be built not only on grand development plans but also on these delicate threads of trust woven by a guest's smile, a story told, a vine offered as a gift to a traveler. Hope does not grow in a void, but in these small crevices created by the encounter of one human with another, and with the beauty of a land the world had long forgotten, or neglected.

A Collective Blueprint for a Mediterranean Future

Turning this dream into reality does not require a miracle, but a collective will and practical steps starting from the ground that bears the footsteps of its sons before investors' maps touch it.

From the government, it requires more than official decisions; it needs a vision that recognizes that investing one dollar in "small guest" tourism may be more successful than a massive project waiting for a customer who never comes. Developing infrastructure means first building roads that connect the visitor to the remote village before the highway, providing electricity and clean water not only to hotels but to homes hosting travelers. Incentives must reach those who open their simple homes as guesthouses, not only those who build coastal tower complexes.

From the local community members, the responsibility is greater, as they are the guardians of memory and beauty. They must realize that their traditional hospitality is their most precious capital, and their smile to a guest is more important than lavish furniture. Creativity could be in a "Stranger's Table" project serving heritage dishes from home produce, a "Grandfather's Tale" tour where elders narrate the place's myths to visitors, or a "Pottery Workshop" reviving their ancestors' craft. Preserving identity does not mean mummification, but presenting the spirit of the place in a language the world understands.

As for opening to the world, it needs cultural bridges that restore to the coast its unifying Mediterranean narrative. Why not have a "Dionysus Festival" for the arts in a mountain village, attracting myth lovers from around the world? Or a maritime tourist trail tracing the Phoenician ships' journey from Ugarit across the Mediterranean? Ecotourism in the forests of Al-Ferliq and the coastal mountains could make Syria a destination for nature enthusiasts, and religious tourism in historic monasteries and mosques could tell the stories of tolerance this land has known.

This coast, with all its contradictions, is capable of being more than just a coastal strip; it can be a model for a society rebuilding itself through its identity, not at its expense, opening to the world without dissolving into it. The soil that ancient sailors carried as a gift from Ugarit to the world's civilizations is still capable of being a message of peace and beauty from Syria to humanity.

The historical opportunity is for stability to be built here not only with weapons and walls, but with the bread a person earns from their land, and with the joy they plant in the hearts of visitors from all corners. The time has come for the Syrian coast to become a space for human encounter, reminding the world that this land, despite all it has endured, still carries the seed of the first vine and is capable of reproducing its joy.

More Than a Destination: A Model for Healing

Syria, with its location resembling the beating heart of the ancient world and its heritage exuding wisdom and civilization, certainly deserves more than the reality of marginalization and pain. And its people, worn by exhaustion, their bodies and spirits accumulated with the aches of war years, suffer a double hunger: the daily hunger for bread, and a deeper hunger for a dignified life befitting their humanity, and for the beauty that quenches the soul's thirst. It is a longing for an ordinary day without fear, for work that provides, for hope that dawns, and for their right to the joy that is integral to their heritage and the nature of their land.

And here lies the role of the coast, not as a mere geographical strip, but as a promise of a different possibility. It offers a unique equation: living history in every stone and artifact, enchanting nature of mountain and sea, and a community preserving its fabric and values despite all storms. This mix is precisely what a world tired of artificiality and similarity seeks. Thus, the coast could become a laboratory for peace through economy and civilization, where people's interests meet the beauty of their homeland, and natural and cultural resources become levers for decent living.

But this path needs a clear compass: a compass that places the dignity and well-being of the local human at the center. Development must be for them and by them, not imposed from outside, turning them into mere scenery in the background of tourists' photos. Successful tourism is where the local feels like a proud host, not a humiliated vendor; a partner in success, not just an employee in others' projects.

The beginning lies in truly listening, not only to the call of international markets but first to the call of deep roots embodied in the story of that grandfather who still knows the secrets of cultivating the vine, and in the nostalgia of that mother who tells her grandchildren tales of the sea. And the beginning lies in turning the dream of the sons and daughters for a future worthy of them into the engine of every plan: a future where the youth finds respectable work in his land, the girl learns a craft inherited through generations and markets it to the world, and the expatriate returns carrying his expertise to build a home on his ancestors' soil.

The Syrian coast, with this vision, will not be merely another tourist destination added to the map, but may become a model for healing. A model proving that exit from the vortex of war and isolation is not through withdrawal into wounds, but by transforming these wounds into wisdom, memory into strength, and natural and heritage beauty into a bridge for communication with the world and a source of pride and sustenance for its people. A better tomorrow begins when we believe this dream is possible, and we start together, step by step, building it from the rubble of the past, on a solid foundation of human dignity and the beauty of the land.

Mohamed Hamdan is an academic who focuses on cultural studies and ancient Eastern heritage.

Comments About This Article

Please fill the fields below.